Unfair – First Impressions

Review copy provided by the publisher

Unfair was the first baby of Joel Finch and Good Games Publishing. And I realize the second child has been born and it’s getting all of the attention right now, but we’re going to put Funfair aside (in a safe and responsible parental manner) and return to the embrace of the eager firstborn. It’s been impatiently waiting for us to remember it and it has done a lot of cool stuff at school today.

Child psychology aside, Unfair is a theme park tableau builder from designer Joel Finch and it asks the player one thing—to not get upset when things don’t go according to plan. Because that’s not how life works and if you want to build the best theme park in the city, then you’re going to have to adapt. You’ve got to break some eggs to make an omelet and you’ve probably got to break some bones and some morale to have the greatest thrill ride and set of attractions the city has ever seen.

Two to five players will be able to jump into this thematic game and you’ll probably be able to finish in about 60-90 minutes. It depends on the level of analysis paralysis that players can experience. The more you play, though, the faster the game will move as you intuitively understand what to grab to make certain card combos.

I’ve played Funfair about eight or nine times and now Unfair has hit the table three times. I’ll be playing it more before the full Right for You / Wrong for You review goes live, but it’s definitely time for some first impressions.

What It Does

First off, players are going to decide what themes they want to showcase in the theme parks. Pirates, robots, and vampires. Or gangster ninjas who live in the jungle. Those are just the first six themes, though. Expansions will eventually fill out the entire alphabet. You’ve got the PRVGNJ mix. But the ABDW expansion is out now and more are on the way. Doesn’t make sense yet? No problem! Just be excited about Aliens, B-Movies, Dinosaurs, and Westerns joining the crazy mix of Gangsters, Jungles, Ninjas, Pirates, Robots, and Vampires.

Why do these themes matter? Because they act as modular decks. Players each select a theme they want and that deck is then incorporated into the game’s stable of cards. Automatically, that indicates a level of variability and complexity that is absent in Funfair. That deck is static. It’s not going to change every game.

In Unfair, however, players have agency in determining what they want their game to look like. Interested in the meanest possible experience? You can do that by finding the more aggressive or challenging themes. Want all the money that you could need for upgrades? Grab the Gangsters theme and find the other decks that complement it the most.

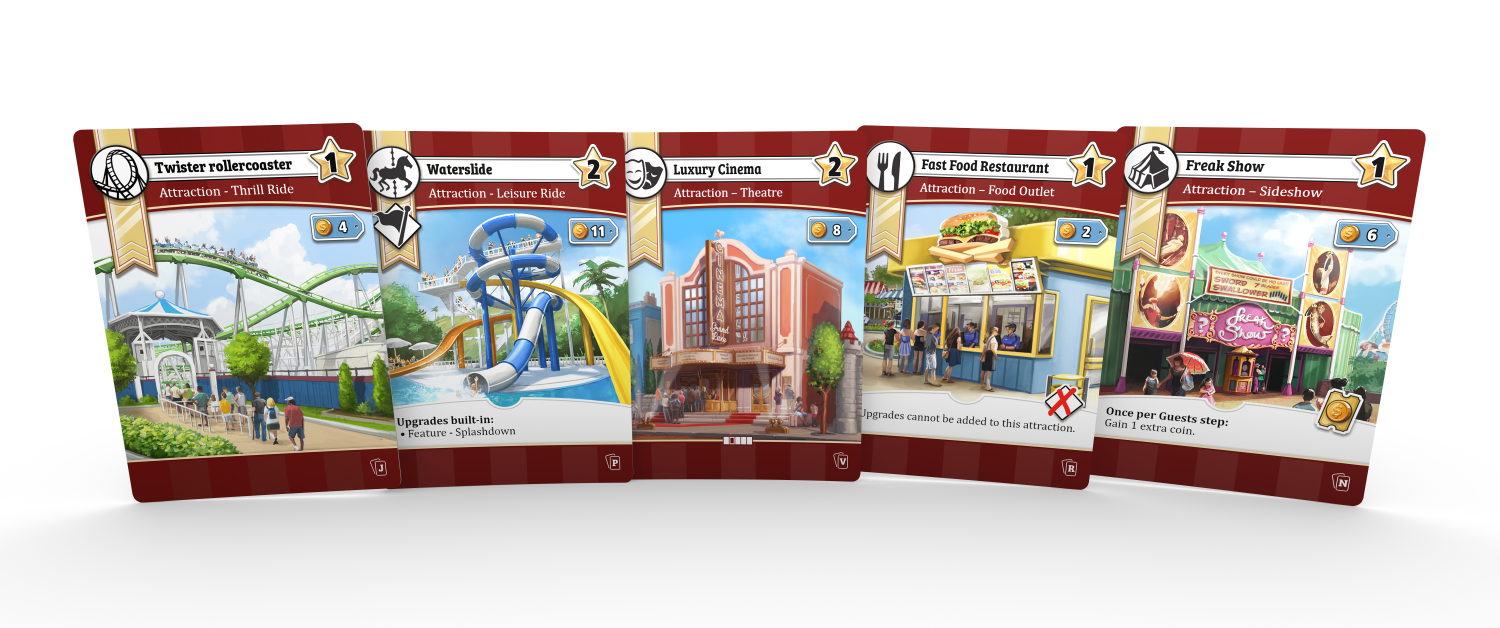

Once the themes are sorted out, then the real game begins as players progress through event phases, action phases, and refresh phases. Events allow players to interact with the game and each other—positive and negative events will occur based on city interactions affecting all players and personal interactions affecting one or more players. Actions are the churning inner core of Unfair, where players will build attractions, select upgrades, and start to fine-tune their theme park in accordance with the parameters of valuable Blueprints. Those cards give a sense of purpose and direction for players to build rather than aimless creation. And then both of those major phases are followed by a brief refresh phase that introduces income and cleans up the shared Market pool and player hands.

After six to eight rounds of that, you’ll finish and the players will tabulate their score using attraction height, Blueprint bonuses, endgame currency, and staff members who provide additional scoring opportunities based on their attributes.

Theme parks are not simple. They are beautifully intricate bundles of steel and raw nerves. Players will come to understand that as they defend their creations against an onslaught of city planning, fierce competitors, and the unfortunate knowledge that the one card they really really need is probably at the bottom of the deck.

How It Does It

Players will start by card-drafting. Each “architect of amusements” will get five cards and that number will fluctuate over the course of the game. Using the private hand and the shared Market pool of cards, players will slowly build a park full of attractions and upgrades.

Tableau-building comes into effect as players place down attractions and then slip upgrades underneath those, growing their attractions to greater heights.

Each player area is divided into the main gate, with the attractions and add-on upgrades to the side and any purchased staff members or resources off to the side. Blueprint cards and Showcase cards do not count toward the player's hand but are also used throughout the game. And then the Event cards, which are powerful tools in the hands of a player, do count toward the maximum card count, which makes the player weigh decisions when thinking about playing, keeping, and combo-ing them.

Players are working on hand management as they acquire the cards they need, keep on to the ones they haven’t built yet, and try to expand their tableau. Set collection is also present but it fluctuates depending on the Blueprint cards. The “set” you want each game will be different, making for a very interesting level of variability and replayability.

And I’ll definitely talk about it more in my full review (as well as the eventual comparison of Funfair and Unfair) but I can’t really ignore the “take that” element of the game—not because it bothers me or overwhelms the other mechanics but because it’s a mechanic on which a lot of people focus. Event cards are really useful for players. They can use them to boost their own gameplay and help secure much-needed gains while building out their park. However, they can also act as attacks or delays on other players, forcing those individuals to get rid of upgrades, pay fines, or face other detrimental circumstances. It’s there. People use it. But there are entire games where you might not see the value in hurting one player more than helping yourself. And it’s an important distinction to realize that the positive and negative event actions are two sides of the same coin. Only one action can be used. Hurt someone else at the cost of not benefiting yourself, or vice-versa. It’s a tough decision as the game progresses because the double-ended Event cards can send a player in wildly different directions (and scoring opportunities).

Technically, you can also use some of the setup modification cards to remove that possibility entirely, but I do want to mention that the powers are more situational than essential. As a wise man once said, with great power comes great potential to probably just build your theme park with the big bonuses on those cards.

Also, I like player interaction so the downside of event cards is an upside in strategy for me as I figure out how to navigate the more treacherous waters of building attractions.

Why You Might Like It

Unfair has so much modular variability. The initial six decks are a lot already, but the potential of the 26 decks that are planned is just crazy talk. It means you can have hundreds of games and all of them play differently. But even if you don’t get any expansions, there is a lot you can do with just the base game.

It’s also got some meaty decisions, as you grapple with the thought of a loan, the value of another Blueprint card, or the combinations of certain Event cards when triggered in the right order. Juicy ideas make real.

Why You Might Not

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room. How did it even get into this sideshow attraction? Anyways… You can negatively affect another player’s progress. For some people, that’s a major turnoff. You can consider the in-game methods of modifying the experience, but it may be a steep ask.

Setting up and breaking down Unfair is not as… fun as Funfair. You have to pick out the theme decks and then separate them out. And then add them to the parts of other decks. And then shuffle them. And when you’re done with the game, you have to do all of that again, but backwards. It’s a little laborious after playing something like Funfair.

Final Thoughts

If I had to pick one of these two games to stay in my collection longterm, it would be Unfair. With the different theme decks, I can customize my experience. With the Gamechanger cards, I can modify or tweak the rules to make the perfect environment for the players at the table. With the expansions coming in the future, I can ensure that this will be a viable option for years to come. With the balanced scale of positive and negative interactions, I can adjust my play or strategy for whatever comes. And with the depth of variability, no two games will feel the same.

I really liked Funfair. But Unfair has a lot that appeals to my playstyle. To my preferences as a gamer. Yes, getting the decks altogether is a little fiddly, but the sheer amount of possibility in that box is impressive.

As a reviewer, I have to churn through a lot of games (and games of those games) in order to produce content. But these two boxes have been a lot of fun to get back out again. I’m still terrible at coming up with a coin economy in the game to finance my attractions and upgrades. But I’m learning combinations of cards and the nuances of themes. All of that discovery is exciting as a gamer.

I’m ready to keep plugging away and learning more.

If you think this is something for you, then check out the Unfair website because it breaks down all of the game and also mentions the ABDW expansion. I’ve been impressed with Joel Finch and Good Games Publishing so far, and I’m excited to see what comes next in the world of theme park tableau-building!

My favorite decks so far? Gangster, Ninja, and Robot. Once the expansion gets thrown into the mix, I’m hoping to be a fan of B-Movies.

Read my first impressions of Funfair, as well as the Right for You / Wrong for You review.

Have you played Unfair before? Do you think you’d prefer this one or Funfair? Which themes would you use?

Let us know in the comments and give a recommendation for other games of which to share our first impressions.